Reflection Between Terra and Heaven, or Where There Human Being Is

Geo-Humanities View in the Anthropocene

An Interview with Masahiro Terada

Terra and heaven reflect with each other; human sphere and natural sphere echo inter-dependently—based on the traditional East Asian view of the world, Jinbun chikyu kankyo gaku (Geo-Humanities), a Japanese book by Masahiro Terada, explores new ways of understanding on nature and culture in the era of the Anthropocene. This interview shows what is the significance of this new attempt.

――First of all, why did you think about to write this book?

Terada The reason why I thought I would like to write this book is simply I have not read this kind of book. I wrote this book, because I wanted to read this kind of book.

Of course, there are numerous books on the global environment or environmental issues, but, in the Japanese book world, there is not so many books which argue it from view point of humanities. It might come from the situation in which natural science dominate the study of environmental issue in Japanese academic world; issues like global warming, degradation of forest, or pollution of water, etc. are very popular topics concerning the environment in Japan—maybe similar to the global situation. In that sense, main arena of environmental study is to measure it quantitatively, and to reveal its mechanisms using natural scientific method. Such kind of area dominates the world of environmental studies in Japan, and actually its development is remarkable. Books based on those method are enormous.

Also, social scientific approach, or so called social commitment holds a prominent position in the studies of environment, like that for sustainability or that of resident participation. Books on those themes are also many. Those researches are done as a part of policy making. The term SDGs is already popular and its colorful logo mark is seen everywhere in shop or as a pin badge on the flap of jacket. Also, in ordinary sense, environmental issue is thought to be a thing of micro-plastic and replacement of plastic bag to the “eco-bag”.

In such a situation, in Japan, it seems to be difficult to imagine an environmental study from view points of humanities. And, actually, books written in such a direction are very much rare, if not nonexistent.

But in the study of humanities, numerous new perspectives emerge. Those trends are closely related with environmental issue. Boundaries between human being, living thing, and thing are blurred, and from such perspective, new ontology is pursued; alternative view on justice and equity of global environment is emerging. But, at the same time, attempt to provide comprehensive understanding of environment from humanities view with including those new tendency is still insufficient. I thought that a book which compiles them is necessary.

――I agree with it. Academic development in the field of humanities relates with environmental issue is remarkable. Present situation might require to adopt it and to update environmental studies.

Anthropocene and Geo-anthropology

Terada Also, another stimulation comes from another continent.

Now, in Europe, a new academic discipline is forming; it calls ‘geo-anthropology’. As the English title of this book, Geo-humanities, shows, it wants to commit such kind of trend, but it wants to do so with slightly different stand point than geo-anthropology.

According to Jürgen Renn, one of the directors of Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, geo-anthroplogy is “the science which investigates the process which leads the Anthropocene.1”

The term Anthropocene has been gradually familiarized in Japanese intellectual world. In 2020, Jinshinsei no shihonron (Das Kapital in the Anthropocene)2 written by Kohei Saito, historian of economic thought especially that of Karl Marx, sells more than three hundred thousand copies.

The Anthropocene is a term which is proposed by the earth system scientists for a name for a new periodization of the geological era. In the traditional geological definition, present day belongs to the era of Holocene, which began around hundred thousand years ago. But they think that present day, especially the period severely influenced by the negative environment effect caused by industrialization and modernization, is no more the same as the days in around hundred thousand years ago. Human being has influence on geological phenomena, hence, they think, that present day should be called the name which indicates such human impact. In Europe, many attempt has been done since the invention of the term in 2000 and with summing up those studies and with searching new direction, new science is emerging.

――As for the reason why Saito’s Jinshinsei no shihonron (Das Kapital in the Anthropocene) becomes the bestseller, I think that, under the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, everyone on the earth is forced to rethink about the relationship between the their planet and humanity. Your book must relate with such situation.

Terada Yes. I think so. The term ‘geo’ in the ‘geo-anthropology’ means the earth, and the term ‘anthropology’ indicates the studies on the human being. In the present, the term ‘anthropology’ is used in relative narrow sense and seems to be treated only as equivalent to the term cultural anthropology or ethnology; whereas, in the 19th century, it has relative broad meaning, and signifies the studies which investigates human being and their surrounding worlds.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), a German philosopher who lived late 18th and early 19th century, for example, wrote an article which discussed the problem of the ‘anthropology’ (1798).

Kant is a philosopher, but he has very rich knowledge in the natural sciences, especially in physics, cosmology, and mathematics; in his Kritik der reine Vernunft (Critique of the Pure Reason) (1781), we can find topics concerning those natural sciences everywhere: in the book, he analyzes the transcendental reason, and the very idea comes from the idea of absolute time and absolute space developed by Isaac Newton (1643-1727). Also, in the argument of four ‘antinomies,’ the main argument of the book, he discusses the problem of whether the world has beginning or not, and whether the world consist of parts or is the one, and others. Those questions are still discussed in the present astrophysics eagerly. Even, in his thirties, Kant wrote an article entitled as “the quest for the principle for natural history in general or the cosmos, and mechanism of the origin of the entire elements of the world based on the basic principle of Newtonian mechanism”(1755)

In his fifties, he lectured anthropology at the University of Königsberg, his affiliated university, from winter semester of 1772 onward. Interestingly, it was coupled with his lecture of geography.

The Kant’s article on the ‘anthropology’ is the lecture record of that lecture series. Its primary focus is on the nature and tendency of human recognition; it can be said that it is rather a philosophical paper than an anthropological and ethnological one. It wants to inquire the question of what kind of nature the human being with free will has in the world where the laws of physics dominates.

In this context, we can assume that, at the beginning, ‘anthropology’ was a study which wants to investigate the place of human being in this world. Kant wanted to know where there human being is in the world through the lens of then contemporary natural sciences.

On the contrary, at the present of our time, ‘geo-anthropology’ wants to do so with confronting the declaration of the era of the Anthropocene by natural sciences; in another word, under a caution concerning the sustainable future. The invention of the term ‘Anthropocene’ questions the relationship between human being and the earth in unprecedent way. The invention of the term ‘geo-anthropology’ is a reaction for this alarm.

The place of human being in the European thought and that in Asia, however, differs slightly. My primary motivation to write the book was how the place of human being is defined from the view point of ‘geo’ namely the global environment in East Asian thought.

Reflection between the heaven and the human being through the bun (letter)

――In your book, you advocate the concept of mutual reflection between heaven and terra, i.e. the sphere of human being, through bun(letter), an East Asian ‘sinogram’ cosomological terminology. Is it that another view, which you just mentioned?did you find another unexpected response for your book?

Terada That’s right. The term bun (文) in Japanese, or wen in Chinese, is very interesting word.

In present, the word bun, or wen, is normally used to the human cultural phenomenon mediated by the language like bungaku (文学literature) and busho (文章sentence). Another usage, however, still remains as seen in tenmon (天文cosmology) or suimon (水文hydorology)—as consonant ‘b’ and ‘m’ often mutate in Japanese, they are mutated words of tenbun and suibun, respectively. In latter cases, bun means pattern, markings, figure, and so on. If we assume latter as some kinds of pattern, cosmology can be defined as the study of analyzing the pattern, or the letter, of the heaven.

In the East Asian ‘sinograph’ sphere, there is a set of words which contain the word bun: jin-mon, ten-mon, chi-mon. Jin-mon is written with two letters of jin(human) and bun (letter). Ten-mon, of ten(heaven) and mon(letter). And chi-mon, of chi (terra) and mon (letter). In the East Asian tradition, concept of ten (heaven) plays an enormous important role.

As the phrase ‘To know the heaven’s mandate,’ one of the popular conventional usages, reveals heaven is thought to be obtain the universal value and rule. It thinks that, from there, the worldly principles are distributed as li (理reason) or ki (気energy). The trinity words of ten-mon, jin-mon, and chi-mon are based on such a world view and signify the reflection between heaven, earth and human-spehre. This view thinks that human being is connected to the world through bun(letter).

――Certainly, in Japanese, Chinese and Korean, discipline of cosmology is translated as tenmongaku, and hydorology as suimongaku. Also, those languages call humanities as jinbungaku. Those Asian names have such common background.

Terada Yes. Those terminology comes from the taxonomy of the disciplines in East Asia.

Also, in East Asian taxonomy of scientific disciplines, there are another distinction between literal studies and scientific studies: bun-kei(文系) and li-kei(理系). Those terms are adjective and adverb. Bun means letter, li natural law, kei ‘related’, hence bun-kei means ‘literature-related studies’ and li-kei means ‘natural-law related studies.’

In East Asia, knowledge is divided into those two branches; University faculties or governmental policy are based on this distinction. It is the basement of the epistemology of sinographic world view.

On the contrary, in the academic world, there are other criteria of disciplinarity. Especially the sciences originated in Western civilization have rigid wall between disciplines. In the age of turbulence, which is not only societal but also environmental, inter-disciplinarity or even trans-disciplinarity is required.

Seen from the view point of bun, a thought based on the Eastern Asian sinograph tradition, problem of environment and the place of human being wherein might be thought in different way than that of Western originated disciplinarity. I think the concept of bun, or humanities, may provide one of the keys to come to the alternative perspective.

――It must be a quest for the another way than the present academic mode.

Terada To focus on the problem of bun leads the way which might be different from that of the modern academic disciplines has developed and archived.

What brought the Anthropocene onto the earth is the modern disciplines, or sciences. When the ‘geo-anthropology’ is a science which investigates the pathway which lead the Anthropocene, the ‘geo-humanities’ might be a science which critiques the pathway which lead the Anthropocene onto the earth from another view point than Western one, namely from that of bun.

Does Nature Talk?

――Bun is a phenomenon relate with language and the way how human being confronts the world. In your book, the term ‘narrative’ has significant importance. What kind of role the ‘narrative’ plays in the studies of environment?

Terada Problem of who talks the environment and how is it talked is the important question in the studies of environment. Narrative is always problematized. It is also a problem of politics. Environment is perceived and interpreted variously by various actor. The difference between every mode should be questioned.

――It reminds me of the concept of ‘Umwelt’ by Jakob von Uexküll (1864-1944), a Estonian biologist and semiologist.

Terada That’s right. As Uexküll says tick has tick’s own world view, dog has dog’s, and human being has human being’s. Furthermore, world view of human being differs from in culture to culture.

――I see in your book a chapter entitled as ‘Does living thing talk?’

Terada It is an epistemic and ontological question whether living thing actually talk or not.

On the globe, there are a lot of folk tales which say living thing talks. Such kind of phenomena seems to be quite natural in those tales. In the world of science, however, you will be despised when you say that living thing talks.

But is it so? Philippe Descola, a French anthropologist, reveals, in his Beyond Nature and Culture, with referring the opositio in traditional logic, that such kind of ‘scientific view’ is neither universal nor logically justifiable. He calls it naturalism. It is difficult for Japanese language to understand the term naturalism, because there has been controversy of what is the nature since the term is introduced into Japanese in the late 18th century. European concept of nature and that of Japan, or sinographic-sphere, are slightly different and how to translate it was itself provocative problem. Naturalism is the view through which present natural sciences see nature as nature. They see trees and animals as elements of nature.

But in the planet, there are another view towards those things; some sees trees as deities, and others see animals as totems. Such kind of views are called as animism and totemism. Science, on the contrary, denies those views and wants to see living thing as elements of nature. It is the foundation of naturalism and the stand point of scientism.

What Descola reveals is that the naturalism, or the scientism, is mere one of the many view points, and, like animism and totemism, it is only one version of various relationships between human being and living thing. It cannot be said that only the scientism is rational and universal, nor animism and totemism are irrational and nonuniversal. If animism is irrational, scientism is also irrational. In such a sense, living thing talks. The book is written from this view point.

――It might also be a stand point of bun. Bun (letter) is a linguistic phenomenon. But the world of bun must not be limited in the world of human being. It must spread or cover other sphere than that of human being, and in such a place, there must talks everything in their own ways.

Terada In the world of natural science, there emerge new discipline, like bio-semantics or bio-semiotics. The situation might be changing.

Agamben, Disaster, and the World

――In the academic world, new trends are coming. Your previous book, What You Are Waiting for on the Top of the Volcano, published in 2015 has a subtitle read as Towards a New ‘Scienza Nuova’ of Humanity and Nature. Have you already seen the new science of humanity and nature?

Terada What motivated me to write that book then was an encounter with L’aperto (Openess), a book by Giorgio Agamben published in 2002, in Berlin.

It was a workshop on the theme of the Anthropocene held in Haus der Kulturen der Welt(House of World Culture), a cultural institution, and I met that book at a mini temporal library in which related books are collected.

Agamben is an Italian philosopher. Although he is not a theologist, he has strong interest in religion, especially Hebraism and Christianity, and developed his philosophical system based on such concerns.

I had already read his works, like Homo Sacer, or Remnants of Auschwitz etc, and above all, the L’aperto stimulated my thought very much.

The book investigates the relationship between human being and the world by being navigated by the concept of ‘openness towards the world’ by Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher. In it, the notion of Umwelt by Uexküll, which I have just mentioned above, is also referred.

When I read that book, however, I did not think that it might relate with the study of environment. The Japanese intellectual world then seemed not to treat problematics which the book provoked as a theme related with global environment, and I might be influenced by such atmosphere.

My reading of the book then was from a view point of how to think about catastrophes. Normally, natural disaster and man-made disaster are distinguished each other, but I thought that when those two are regarded as a catastrophe in broad sense, what should be questioned might be the ‘catastrophe-ness,’ or the nature or the essence of catastrophe, and there might be no clear boundary between natural disaster and man-made one. In L’aperto, Agamben argues the problem of Auschwitz, on the one hand, and discusses the problem of Uexküll ‘s Umwelt, on the other hand. If so, where his book directs is a way in which dichotomy of nature and artificiality is abandoned. He discusses not only the problem of catastrophe, but also more universal problem between human being and the world.

Japanese reader, however, seems not to read it in such a way, and, above all, there seems not to be such a discussion concerning the world and human being in Japanese intellectual world.

In Berlin, at that library, there was a reading in which Agamben and the problem of human being and environment are closely connected.

Agamben’s L’aperto is not a book easy to read. Agamben is a difficult philosopher to approach. But, there in Berlin, such a philosopher is read under the light of the concept of the Anthropocene. It was eye-opening experience for me and an encouragement.

The notion of the Anthropocene comes from natura science; it is based on the Earth Systems Science, which can be said as a very essence of natural science. On the contrary, Agamben is a north pole of humanities. Those two are connected closely in the library of HKW in Berlin. It was as if I found a key in another continent. That key would open the door towards a new thinking. It was mere a presentiment. But it seemed very much secure for me. The subtitle of my previous book, ‘Towards a New Sicene,” reflect such kind of feeling I had in Berlin.

New Sciences

――It is a transitional phase of sciences now; the emergence of the Anthropocene concept might be a symptom of such an era. There are various attempts to look for alternative way.

Terada Yes, indeed. Even if limited in humanities, we could count many examples which provide new views on human being and environment: Actor-Network Theory by Bruno Latour, multi-species ethnography in anthropology, manifest of cyborg in STS, ‘Object Oriented Ontology’ in metaphysics, etc. Environmental studies should be updated with adopting those new approaches and methods.

In addition, environmental studies should enlarge its scope beyond the area which was thought to be a proper area of it: mesology by Augustin Berque, study on recit(tale) by Sadakazu Fujii, primatology developed by Kyoto School which is originated by Kinji Imanishi, Jun-ichiro Itani, and developed by Masao Kawai, Juich Yamagiwa, Kazuyoshi Sugawara, and others, ‘lemma-logy’ by Shin-ichi Nakazawa, mythology by Claude Levi-Strauss, capability approach by Amartya Sen, Human Sustainability Index by Center for South East Asian Studies of Kyoto University led by Kaoru Sugihara, Eco-health study by Kazuhiko Moji, and so on.

This book wants to integrate them into single package.

――It is ambitious attempt. But is it possible to integrate them,or synthesize them?

Terada It might be impossible to do so. But only to line up and showcase is not enough. In order to narrate it as a new science, a line which penetrates them is required. This book adopts two strategic viewpoints; one is focus on problem of human being, living thing, and thing, and the other is problem of the world and the emergence.

Human being, Living Thing, and Thing

――Those terms appear on the subtitle of your book. Is the reason why you choose the words ‘human being, living thing, and thing’ might be that they imply that environment consists of them? Do they indicate that this book thematizes the environment as such constructed entity?

Terada Yes. And, at the same time, the book intends to revise the boundaries between those three.

――What kind of boundaries do they have?

Terada Normally, it is thought that there is a boundary between human being and living thing. And a boundary between living thing and thing thought to be exist. However, are there really boundaries? I mentioned the term mesology above. Mesology, or the science of ‘meso,’ i.e. betweenness, developed by Augustin Berque, a French philosopher and human geographer, wants to re-investigate boundaries thought to be there in our environment. Western scientific view, whose origin comes from Aristotelian metaphysics, thinks that there are boundaries in the world of things. But, on the contrary, there, in the world, is another view, which does not think there are boundaries in the world of things, like that of Nagarujuna, a Buddhist philosopher, said to be in 3-5th century AD in India. His doctrine of the middle way thinks that the world consists of not things but is affair or phenomenon; there is no boundaries and there only is succession of gradation, namely the middle-ness. As the rise of the mesology indicates, in the present, in the studies of environment, boundaries between human being, living thing, and thing itself is questioned.

The World and the Emergence

――Also your book has another view point; what kind of implication does the term ‘the world and the emergence’ have?

Terada The world is what surrounds you. It is a phenomenon and is categorized by the surrounded in every moment. To draw a line between human being and living thing is a categorization, and to draw another line between living thing and thing is also a categorization. They appear in the world in every moment as a phenomenon between surrounded and surrounds. The term ‘the emergence and the world’ indicates this functional relationship. I think to investigate it closely must tell us a lot about the foundation of the world, and we should be much more attentive to such dynamic relationship.

On the dust jacket of this book and on the opening pages of every chapter, Arboreal, an artwork of Rohini Devasher, an visual artist bases in India, is seen. Dialogue between she and I is also read in the book. Her work embodies the problematics of the emergence and the world.

In our conversation, the artist developed an interesting term: ‘the green house of possibility.’ With using this phrase, she wants to reveal that the world is a bundle of possibilities. To see the world as something open to possibilities bring us an active tendency towards the world. And to think about the existence of possibilities is to imagine alternatives.

Global environment studies is a science which is closely connected with the problem of how to think about future. The concept of sustainability presupposes sustainability in the future. Of course, global environmental studies has another raison d’etre, like to know the place of human being in the world, but it also cannot be detached from the question of how human being will and should live in the future.

In this sense, problem of ‘the emergence and the world’ touches the core of the environmental studies. To follow the path which it directs us might be also a pathway to the geo-humanities.

Narrative of Terra

――This book is published as a second volume of the series of ‘Narrative of Terra / Terra Narrates,’ published by Airi Shuppan. You are the series editor of this serial volumes. How do you think about the future of this series?

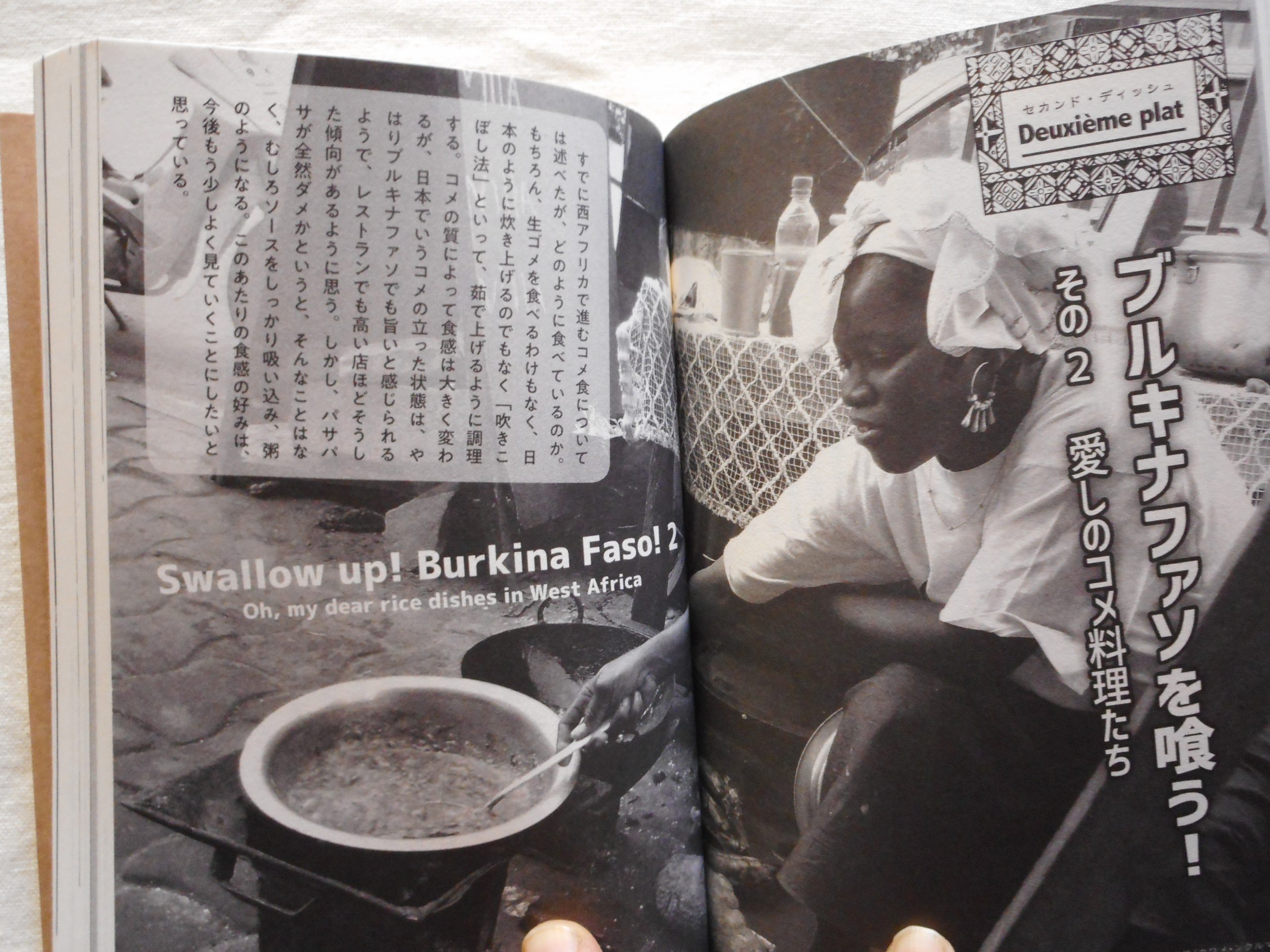

Terada The series launched with Takao Shimizu’s Swallow Up, BurkinaFaso! in 2018. It is very positively received by Japanese readers; book review of many major Japanese newspapers picked it up with good evaluation. My book is a second volume of the series. I hope that mine also follows the same way as Shimizu’s.

I am very much confident with the page layout and design by Naoko Kamise from Teisuisha, and the design of dust jacket and cover by Shin-ichi Wade from Shotousha and an active member of Living Montage, both of whom are our ‘series designer.’

The editing of the third volume and the fourth have already begun.

――I am looking forward to reading them.

—

1 Jürgen Renn, The Evolution of Knowledge: Rethinking Science for the Anthropocene, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2020.

2 Kohei Saito, Jinshinse no shihon ron(Das Kapital in the Anthropocene), Tokyo: Shueisha, 2020, in Japanese.