Living Montage:

The Margins of the Field Research

Kenichi Sawazaki (Artist, Film director)

Field research is academic research that uses research techniques such as physically visiting sites appropriate to the subject or theme of the research, directly observing the subject, interviewing the people involved, conducting questionnaires, and collecting historical documents and materials in the field.

Sawazaki has been involved in producing and presenting contemporary artworks, but the production of a documentary film about the activities of the French gardener Gilles Clment(Figure1)*1 led him to produce many videos documenting the fieldwork activities of Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN) researchers in Japan and abroad. He has always been interested in exploring the expressive possibilities that arise from the experience of fieldwork. This essay explores that artistic practice.

Figure1 : Gilles Clément in the film The Garden in Movement

Artistic practices that treat the “margins” of the field as if they were the “centerpiece”

In the age of mechanical reproduction, the “Art Autonomy” became an issue when art no longer had the “Cult Value” associated with religious beliefs, but the separate “Exhibition Value”*2. But with the recent development of transportation and printing technology and the advent of information technology, art autonomy from the social context can no longer be achieved, and many forms of artistic expression have emerged that deal with the relationship to society and its margins. In this context, if there is something that characterizes art today, it is the way in which the artist concentrates his or her creativity on how to focus on social phenomena and how to express these phenomena as art to draw society’s attention to them. Art is nothing more than a view, a unique way of looking at the world that is already in front of us.

In a lecture entitled On the Origin of the Work of Art in Mesology*3, geographer Augustin Berque (1942-) attempted to explain Martin Heidegger’s (1889-1976) The Origin of the Work of Art (1935) in terms of the doctrine of Mesology or Umwelt. According to Berque, Mesology is the doctrine of the relationship between man and nature, while Umwelt is the doctrine of the relationship between living beings in general. The Subject (S) that underlies the world has no meaning in itself for man and requires a certain process to give it meaning, namely the predicate (P). This is expressed by Berque as S/P (S as P). The subject (S) appears as the predicate (P).

As a more direct example, Berque cites Heidegger’s use of the image of a temple. The temple was built on the rock, and through its work the world came forth as world. Where did it come from? It came from the world itself, as “something”. Without the work of this “something,” it would not have appeared as a “something,” that is, it would have had no meaning, and therefore it would not have existed. In the case of the temple, the ground (S), the foundation, was used as the basis of the temple (P) so that the temple could exist. In the process of constructing the temple, the world appears as the world and takes on the meaning of being the world. The temple is a work of architecture, a work of art. It functions as an “opening” for something that is an S. This is how we can explain the origin of the work of art.

Sawazaki has already mentioned that today’s art is characterized by the way in which the artist concentrates his or her creativity on how to focus on social phenomena and how to express these phenomena as art to draw society’s attention to them. It can be argued that human imagination should be applied to “how” to “open” the world to be the world and how to build a temple. The search for this “how” is a practice that has to do with the origin of the work of art.

And if we apply what we learn from Berque to fieldwork and look at it, we can see something like the following.

At the researcher’s field site, in addition to the behaviors being studied, there is much “potential for shaping the future of society,” such as the wisdom, ingenuity, and surprise that can be seen in everyday life. Researchers are people with very advanced and specialized knowledge and skills, but they also have the opportunity to learn much of this potential, and their results reflect some of these things. However, although we may feel that a very small event has potential, it can only be described episodically in an academic paper, and the sensory and emotional experiences in particular are difficult to incorporate into an academic format.

Is it possible to document such “potential” in fieldwork, that is easily positioned as being ”marginal” to research findings in the academic context, through visual media and see it as “central,” sharing its potential as an object of appreciation and evaluation from a perspective outside academic media? To paraphrase Berque: If it is the view of a field researcher that “Opens” a “Way of Life (S)” as a “Way of Life with Diverse Potentials,” could we not create another view to “Open” as a different “Way of Life” (P) by returning it back to the view of the researcher? The attempt in this work is an artistic “Return” to find a “Way” to “Open” the way of life of people seen by the researcher in fieldwork as having a rich potential, to be something else.

A method born of a life in constant movement and having the “Eyes of the In-Between”

In Sawazaki’s experience, today’s way of life, where “life itself is in continuous movement” rather than rooted in a particular place, impairs the sense of engagement with events. But even in continuous motion, there are times when the relationship created by the camera causes us to feel involved in the inevitability of the event. In this case, the relationship is created from the perspective of being “suspended” “in-between” when one is neither an interested party or a non-interested party. We refer to this perspective as the “Eyes of the In-Between”.

Whether or not a person has directly experienced an event is the boundary line that separates an interested party from a non-interested party. We can say that being “in-between” is an indirect experience of an event. Moreover, when we say “in-between” something and something else, that something and something else are qualitatively different. For example, we could say that we have cross-cultural communication “between” different countries and peoples, where the “Eyes of the In-Between” is “between” different things.

If one is to relate to events and cultural practices with which one is not directly involved, this must be accompanied by one’s own active will, judgment, and action. Of course, this positive attitude must be accompanied by a strong motivation, such as the desire to experience something. The “Eyes of the In-Between” is a view that sits between two different visual systems, but is not dependent on either, and yet “tries to see things positively.”

This happens whenever you try something out. When people from different cultures spend time building a relationship with each other, we can expect that the interaction between these cultures will produce a different culture, a mixture of both. But if this creates a solid community, then there is no more “in-between” in the situation. For this reason, the “Eyes of the In-Between” contains the feeling of being suspended in the air before different things mix.

In relation to this “Eyes of the In-Between”, Sawazaki has been exploring ways to use video to get people to reflect on their experiences in the field related to fragmented “life itself” by recording their lives, without drawing them into a particular narrative or theme, or assuming an ending as we do in our own lives. The most important element is the “horizontal montage” approach, which does not allow the viewer to determine the meaning of the images.

The term “horizontal montage” was coined by film critic Andr Bazin (1918-1958) as an editing technique with voiceover and was used by Chris Marker (1921-2012) in Letter from Siberia (1958)*4. In Marker’s film, the same sequence of images is repeated like a broken record, with various commentaries inserted into the sequence through voiceover.

If we were to apply this to the work in this essay, we would suggest that a “horizontal” edit, in which different narrative texts, such as the perspectives of the researchers, locals, and cameraman, are inserted into repeatedly collected video sequences using voiceovers, would be appropriate to “suspend” the perspective of the subject of the film. This is because by narrating the same experience of the field from different perspectives, the experience fluctuates beyond a single interpretation.

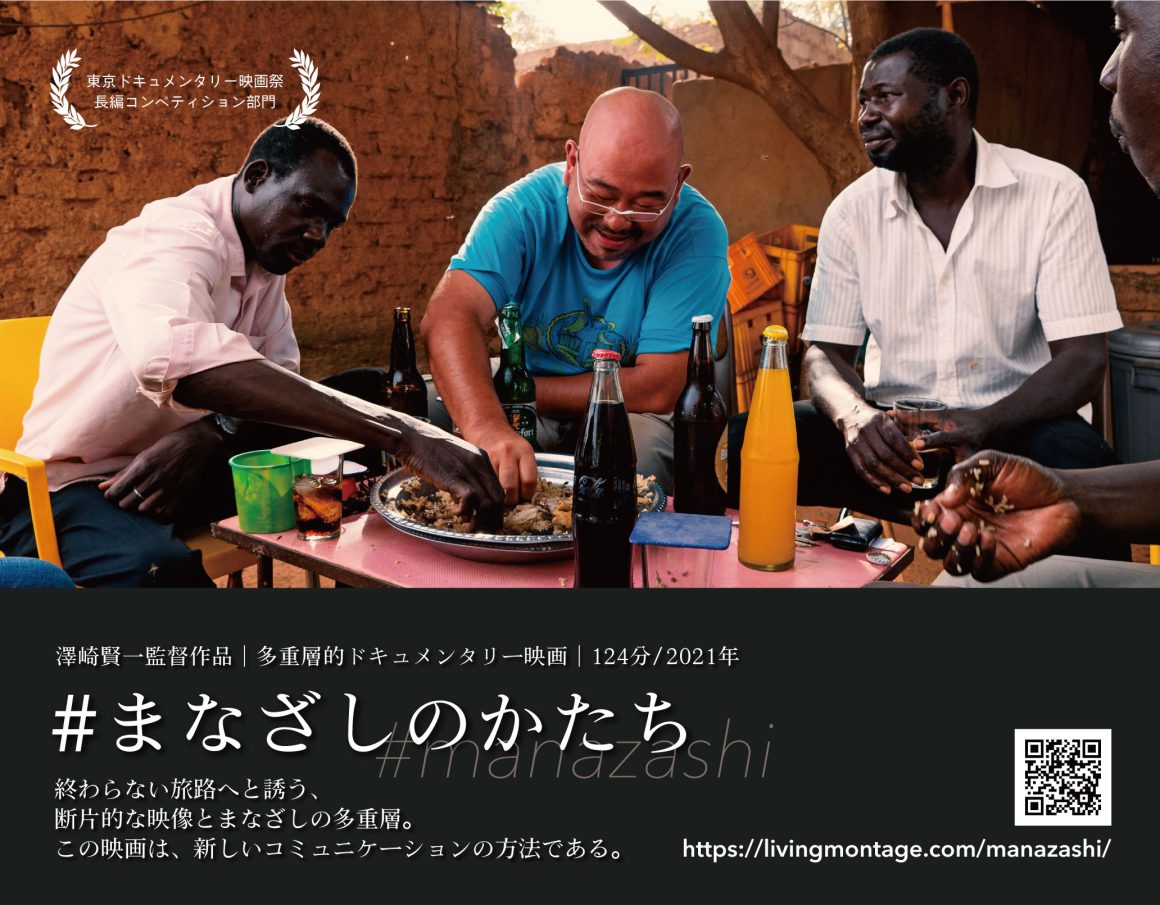

The varied video work #manazashi

#manazashi(124min, 2021), a video work that uses methods from the “Eyes of the In-Between”, is based on footage documenting various human activities in Africa and Southeast Asia, the site of research by agronomist Ueru Tanaka and cultural anthropologist Takao Shimizu(Figure2). To capture the “margins” of the field, Sawazaki filmed the field as fragmented scenes that could not be assembled into clear narratives or themes, and then added unique cuts and post-processing to create a varied film.

Figure2 : #manazashi‘s web poster

There are two narrators in this work. The first is the cameraman, who records the activities of people in the field and murmurs about his own experiences, and the second is the viewer, who watches and speculates on the footage shot by the cameraman. Both narrators try to creatively read and understand their own visual experiences, which sometimes overlap and include fictional transformations as in a novel.

In this essay, Sawazaki presents the video work “After the Rain, Horizontally, On the Street”(10min, 2021), which is a re-edited version of part of the work #manazashi.

A to think about “Ways of Life” through video

At the heart of today’s video experience is what we ourselves record and edit in our daily lives; we see the fragmented images we ourselves record. Therefore, #manazashi, which was created in the same way, asks the viewer what kind of creativity lies in the everyday act of “recording, editing, and viewing videos” and what this visual experience means for human society.

In the context of contemporary society, the boundaries between “moving” and “where you belong and live” are intertwined and indistinguishable.” #manazashi aims to capture the tension between “living” and video work in the process of “moving” through different realms, both physical and mental. It is an attempt to find a to think about something by using the mechanisms of video rather than viewing the video for a specific purpose. This attempt will be continued in Living Montage.

Living Montage proposes a new model of visual media and viewing experience in relation to fieldwork. The practice begins with a where these three things are compatible: the documentation of specific investigations by fieldworkers over time, the perceptual representation of what is in the “margins” that become visible as a result of the investigations, and the artistic expression that is primarily concerned with such “margins.” Living Montage has been built as a platform, like a toolbox, to collect video footage of different people in as many fields as possible and document their human activities, and the products that emerge from the toolbox according to context and audience have been created…

Living Montage needs to be a more flexible and playful platform that, while starting from artistic practice and academic research, does not further restrict itself to these contexts. This is because we believe that only a playful approach to visual media will allow “marginal” experiences in the field to bring new perspectives to artistic practice and academia. Living Montage is a where we can think about our own “Life” through video, without being limited to a specific field.

—

*1 The Garden in Movement, HD, 85min, 2016, http://garden-in-movement.com

*2 Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1935

*3 Forum franco-japonais sur la culture et l’environnement, De L’Origine de l’oeuvre d’art en mésologie, Institut Français du Japon – Kansai / Kyoto, Friday 16 October 2015, https://youtu.be/VGnWIsW2CJM

*4 Chiba Fumio, The Virtual Book, or The Combining Art of Chris Marker, Chris Marker, cinéaste nomade et engagé, p.221, Shinwasha, 2014

*This article is reprinted from the previous paper Kenichi Sawazaki, Living Montage: The Margins of the Field Research, “Toitoutoi Vol.0”, Center for the Promotion of Interdisciplinary Education and Research, Kyoto University, 2021, pp.82-89