Guidebook as an Ethnography:

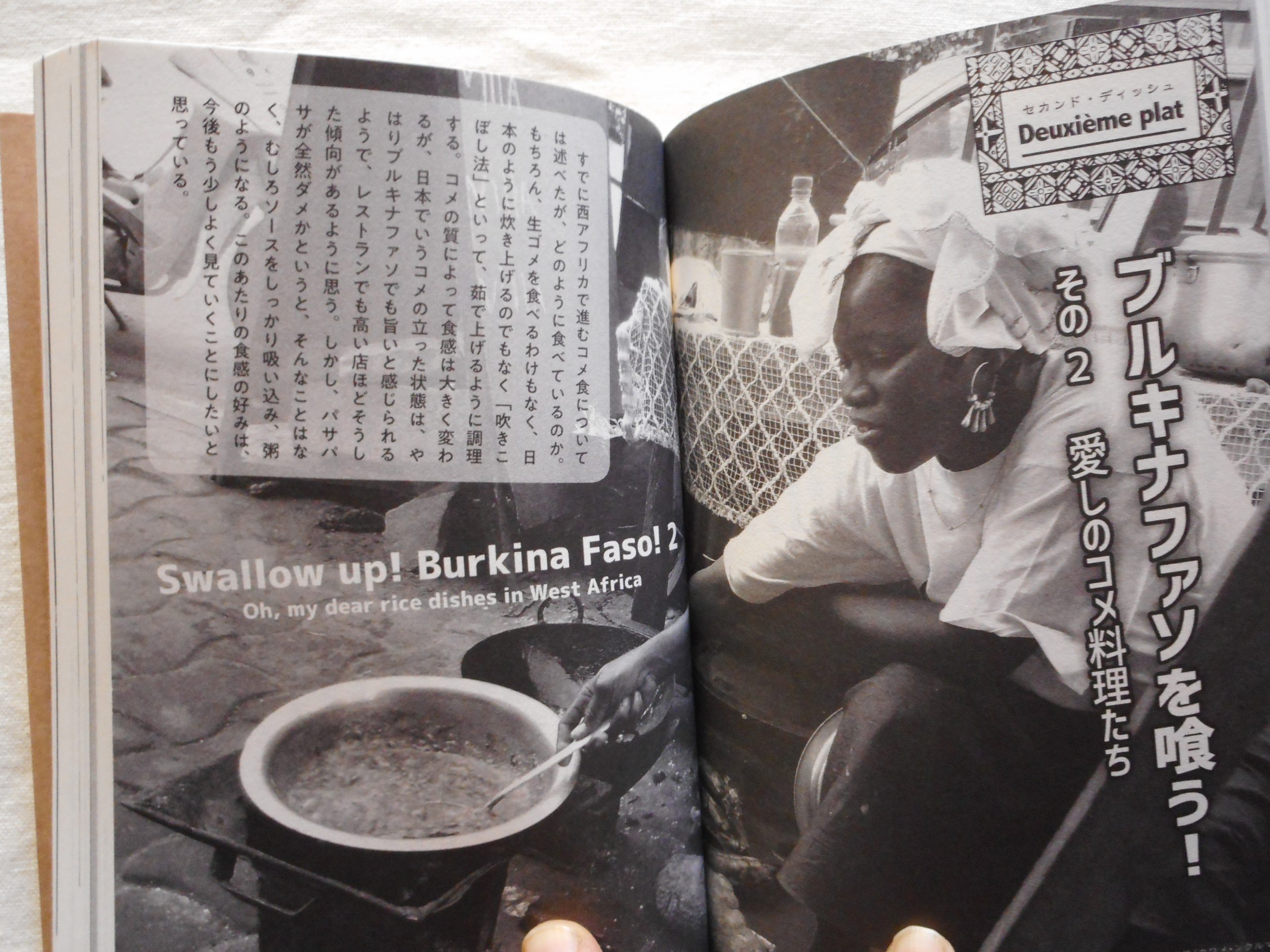

On Takao Shimizu’s Swallow up! Burkina Faso!

Takao Shimizu, Masahiro Terada, and Seiji Nakao

The series of ‘Narrative of Terra/Terra Narrates’ inaugurated with Takao Shimizu’s Swallow up! Burkina Faso! : An Anthropological Guidebook of West African Gastronomy in 2018. It is very well received by Japanese intellectual world and many book reviews on it appeared on Japanese major newspapers.

It is a unique book in that it is the first comprehensive book which provides Burkinese/West African cuisine in Japan. Furthermore, seen in the global perspective, it might be the only book which is specialized in such a topic.

If so, what is the significance of this book? Takao Shimizu, the author, Masahiro Terada, the series editor, and Seiji Nakao, anthropologist colleague of Shimizu, talk about the rich implication of the book.

Takao Shimizu

Associate Professor of Kyoto Seika University, Kyoto, Japan

Masahiro Terada

Visiting Professor of Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan

Seiji Nakao

Assistant Professor of Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

Seiji Nakao This book has a pretty unique style because it combined the autobiography of Shimizu-san and the ethnography on the food culture of Burkina Faso. He integrated these two elements to describe the experience and understand the field through food in his life history. The book is not merely an anthropological study on food culture but also the new style of ethnography, which, in my opinion, does not exist so far. Furthermore, it is very readable for non-academic readers and offers the basic knowledge for Burkina Faso. Major Japanese newspapers picked it up positively in their book reviews. Shimizu-san, did you expect such a response?

Takao Shimizu Not at all. I even suspected whether this book can sell more than hundred copies. And, at first, sincerely said, as an academician, I hesitated to write this book, because I even have not finished my PhD thesis yet. This book is rather ‘un-orthodox’ taste, and I think I should not publish such kind of book before publication of my PhD monograph. I hear that my doctoral supervisor evaluated this book positively. It relieves me very much. He praised this book, because my book is based on my field research and is very detailed. To hear his comment, I could be convinced that what I have done is not false.

How to Think about the Problem of Taste

Nakao Shimizu-san, did you find another unexpected response for your book?

Shimizu Some social anthropologist colleagues complain that, although the book is subtitled as the ‘guidebook,’ it is by no means a ‘true’ guidebook. The book focuses on ordinary foods on the street, and, for them, such kind of things are not worthwhile to be written in a guidebook; those foods seem to be too much ordinal. I think, in their field work, those anthropologist colleagues may not have any joy to eat such food and those food are not attractive at all for them. On the contrary, in my book, I describe such ordinary foods with my sincere love. To hear their complaint, I realized deep gap between I and those people.

Nakao You took up ordinary foods, not only so-called ‘traditional’ dishes, and described them in detail. Your thick description is so impressive that your book deserves to be called an ethnography of food culture in Burkina Faso.

Shimizu The reason why I adopt such kind of description strategy relates the fact that this book is also written as my biography. Actually, the first thirty pages of this book are on my life history; there, I wrote what I have eaten since my younger days. I have been already affected to eat in my early teen days! My affection with African cuisine should be understood on the extension line of it.

In general, for anthropologist, field research in abroad is an ‘extra’ ordinary event. But, at the same time, food eaten during the field research is a phenomenon of ‘ordinary’ life in a sense. I think this dichotomy is a metaphorical meaning. For me, as an anthropologist of Africa with more than twenty year’s career, African cuisines are already ‘ordinary’ things, but, at the same time, they are still ‘extra-ordinary’ for me even today. This book reveals such an ambiguous tendency towards food. It might offer particular interest for some reader.

Nakao Terada-san, as the series editor, how do you find the characteristics of this book?

Masahiro Terada I think what is most significant of this volume is that it focuses on subtle differences of tastes in detail. For example, the author wants to describe difference between tô (pancake in West Africa) made of maiz and that which made of sorgam in taste, flavour, and feeling in the mouse, etc. Shimizu does so in delicate way as if he is writing the taste of French dishes or traditional Japanese dishes served in five stars restaurant.

Nakao The description of taste is challenging, especially when most readers do not eat the food. It does not exclude subjective elements and requires the vocabulary for the readers to imagine the food. But Shimizu-san dared to tackle it. You wrote the personal experiences to eat as your life of field and home. One of the reviews says that this book can be read as a ‘buildungs roman’ of a young anthropologist. I agree with him. Doing the fieldwork and writing papers is a life of an anthropologist, but, simply because it is a life, at the same time he also eat the foods and digest the experiences and the dishes in the field and at home.

How to Hear the Narrative of Terra?

Nakao This book is published as the first volume of the series of ‘Narrative of Terra/ Terra Narrates.’ What kind of implication does the series have in the context of environmental studies?

Terada Notion of narrative problematizes who narrates and how it is narrated. This series thinks that the terra narrates metaphorically. The earth is a thing and, at the same time, is a place. On the earth, there are a lot of narratives. What humanities as a scholarly method is doing is to hear those voices in various places on the planet. This series wants to compile such experiences of scholars. When compiled, those voices will be a constellation or will be synthesized voices.

Nakao Shimizu-san, how did you write these voices in in your book?

Shimizu I was given huge freedom in compiling my texts. Many texts are adopted my personal web log. Terada-san as the series editor suggested the outline, and, after that, I constructed my own narrative by myself. During the editorial process, Naoko Kamise from Teisuisha, an editorial agent, helped me a lot with critical advices. The series editor give advices with rather much less critical attitude.(laugh)

Terada I thought that what series editor should do is to help the author to write by pointing out positive side of his text.

It is often said that, in Japan, editors of popular science book tend to have less commitment than those in English speaking countries. Japanese editor is said to adopt ‘laissez-faire’ strategies in the editing. On the contrary, editors of popular science books in Europe and USA are said to commit deeply in author’s writing from the early phase. I want to do the editing in European and American way rather than Japanese one.

My commitment covers not only the editing, but also the book design. Naoko Kamise—she does not only edit, but also do page layout—and Shin-ich Wade from Shoutousha provided marvelous design for book, dustjacket, and cover.

Nakao The design of the dust jacket is very much appealing and catches the reader’s attention with solid power.

Terada The designer and I made effort to amplify the charm of Shimizu’s text and to transfer it to reader. In the book review of the Yomiuri Newspaper, Nobuhiro Minaka, famous book reviewer of natural science, wrote that the book is beyond the good job. To read it, we feel that we are truly beyond joy!

Not as an Exoticism, but as a Flat Relationship

Nakao I am also an anthropologist studying the history of Burkina Faso. So, I cannot imagine how people read this book, who has not been there. Terada-san, you also do not have experience in Burkina Faso. What kinds of impression do you have?

Terada In my short essay appeared on the Kobe Newspaper, in which I introduced this book, I wrote that the book wants to write Burkina Faso under the light of a flat relationship.

I found some reviews writes that, although the reviewer does not think that he/she might come to Burkina Faso in the future, he/she feels strong interests in the foods described in the book. Minaka also wrotes in his review that, by reading this book, his sense of sympathy stimulated.

Those feelings represent that the reader sees Burkina Faso not as an object of curiosity or of incomprehensibleness, but as something which exist somewhere on the same niveau in this planet with compassion.

Nakao It is interesting. The feeling that ‘I never go there, but I understand that there is such a world’ seems similar to exoticism and orientalism. But the feeling must differ from them. I think of it as a “feeling of the contiguous (地続きjitsu-dzuki).” Most readers of this book might think that Burkina Faso slightly differs from their own lifeworld, but they do not think it strange. Simply, they might understand that there is such a lifeworld. It is different, but it is contiguous to ‘ours.’ The book gives this kind of feeling.

Once, the classical ethnographies had the framework of ‘initiation’ in their narrative. At first, in such a plot, a young graduate student went into a strange circumstance and had difficulties there. However, in the course of the fieldwork, he/she understood something related to the “core” of the society or culture, and made a good relationship with the people there. Finally, he/she returned to home country to finish his/her dissertation. It was a classical story of ‘initiation’ to become a professional anthropologist.

On the contrary, this book is not such a ‘go and return’ story, instead the continuous ‘going back and forth’ diary. Shimizu-san goes back and forth between Japan and Burkina Faso restlessly; for him, such traffic became his daily life. This book snaps shots every day of him. His pendulum way of life between Japan and Burkina Faso will continue; hence, it is also the snapshot of his entire life.

Fieldwork in remote counties has become much easier now compared to before. These changes require a new plot of ethnography. In my opinion, Shimizu-san presented a unique style of ethnography reflecting the actual condition of anthropological fieldwork in this book.

Problem of Voice and Guidebook as Ethnography

Terada I think what fascinates reader of this book might be Shimizu’s literal voice. It must be worthwhile to think about what kind of attractiveness his voice has.

In academic writing, the role of literal voice seems not to be so seriously discussed, whereas in literature, it is treated as crucial matter; as for the recent example, in The Owl Takes Off in the Twilight by Haruki Murakami and Mieko Kawakami 1, the problem of voice in the literature is deeply argued.

At first, they discuss the voice in the physical world; it is a wave of the sound. When the length of waves multiples, they synchronize. Those authors analogize the literal voice with the physical voice. They say that, if multiple voices synchronize, it is a ‘good voice’ in literature.

I think Shimizu has such a voice and his voice makes reader’s inner voice to synchronize it. The feeling of the ‘flat relationship’ might come from it.

Shimizu During my writing the book, I always think about how to make reader understand me when they read my text. Normally, reader does not know me personally, and they know me only by my text; my text is the only way for the reader to understand who I am. So, I concentrate on how to deliver my text to my reader efficiently.

Nakao I think that Shimizu’s book is composed of the synchronization in the voices of the author, the series editor, and the designer. These synchronized voices must attract reader. The design and structure of the book are closely related to the text.

The structure is fascinating. All the chapters have names of dishes; it begins with ‘aperitif,’ and continues with ‘hors-d’œuvre’ and ‘plat premier’ like a French course meal. In the ‘aperitif,’ the chef, namely the author, posed his earlier life story to go to Africa as a starter which brought the readers to the ‘hors-d’œuvre.’ As the ‘hors-d’œuvre,’ he showed actualities of Burkina Faso, and gave the basis of its food culture in the ‘plat premier.’ Of course, he did not forget to serve ‘boisson’ between the ‘dishes’ for depicting the daily life of a young scholar. So, the readers tasted the book as dishes of five stars restaurant! The structure is echoed with each dish’s tempo and theme, making synchronized voices in a ‘well-tempered’ tuning.

Terada When you write a book, the problem of who is your reader should be addressed at first. Tetsuya Suzuki, the editor in chief of the Kyoto University Press, once says that, in writing a book, author should put in range readers in relative broad circle than the primary target. He describes such reader as the ‘reader in three or firth outer tier.’

Nakao Scholars, especially in humanities, try to explore writing techniques for readers. The book explored new potentials to write ethnography as a guidebook in terms of new techniques. I think the potential is two ways; one is to write an ethnography as a guidebook, and the other is to write a guidebook as an ethnography.

Shimizu-san might not have intended to rethink the ethnography, and he just had fun writing a text in such an exciting style. Still, I think, due to the synchronizations, he explored a new genre of ethnography that had not existed ever since.

Shimizu I did not expect that my book would be read in such a way. You read my book as an ethnography. It is completely beyond my expectation.

Terada In the study of anthropology, a lot of new approaches are emerging; one of the examples is visual anthropology which challenges to open a new way to ‘write’ an ethnography in the visual form. New era of ethnography might have been inaugurated, and this Shimizu’s book can be read in such a context.

Shimizu A typical guidebook for ‘remote’ area, like Lonely Planet, is normally written by writer who has enough knowledge on that area, and such a writer is often anthropologist.

But, for a long time, I have had a prejudice that to write a guide book might not be a ‘true’ work for academic scholar, but, rather, only mere ‘job’.

The title of my book has the term ‘guidebook.’ When Terada, the series editor, proposed the term, I was a little confused and irritated, and I could not understand the reason why he proposed so.

But, today, our talk so far told me that a guidebook could be an ethnography. This book is not only about the dishes of Burkina Faso, but also about my research and life; I think that such contents might enable my book to obtain an ethnographic taste.

Recursions in a Book

Terada The reason why I proposed for Shimizu’s book to have a term ‘guidebook’ in its subtitle comes from my experience. I myself have already published a guidebook. It was a guidebook on museum, especially the museums whose focuses are on the theme of war and peace. The main target reader of the book was high school and junior high school students. The book was published in 2005 and it was very well received by reader.

From my experience of writing a guide book, I learnt that it is a kind of critique. And, I also noticed that, in order to write a guide book, author should unify his/her collected data in particular format. Guidebook necessitates homogenization, however, it also requires the author to obtain his/her own ‘unhomogenized’ world view. In this sense, a guide book is a work of expression of the author.

I think that guidebook has many similarities with encyclopedia. It is said that French Revolution was led by Encyclopédiste like Diderot and Voltaire. Encyclopedia has a world view and even changes the world.

I think Shimizu’s book is not only the guidebook, but also an encyclopedia; not only an encyclopedia of Burukinese dishes, but also encyclopedia of Shimizu Takao himself; the book begins with his autobiography! (laugh)

Nakao The metaphor of encyclopedia reminds me of “La Biblioteca de Babel (The Library of Babel),” a short story by Jorge Luis Borges (1944). The story itself is a part of the book in the library narrated in the book; the parts and the whole are nested by each other infinitely. In other words, in this novella, micro-cosmos and macro-cosmos recurse, and the structure of a library and a book reflect each other.

The relationship between Shimizu’s book and the series of ‘Narrative of Terra/Terra Narrates’ is such a recursion, or ‘nested-ness.’ The book is the first volume of the entire series as an ‘aperitif,’ and the structure of the series as the French course meal is reflected in the book. (laugh)

Shimizu I think, as an ‘aperitif’ of this series, my book would enough stimulate reader’s appetite for reading! (laugh) I know that, in the series, there come varieties of dishes. I believe that my book would have started the course in a good manner!

Nakao As a reader, I enjoyed the ‘aperitif’ very much, and it makes me to be looking forward to reading coming volumes! Thank you, Shimizu-san and Terada-san, for joyous conversation!

*This text is translated by Masahiro Terada from following Japanese original version: Takao Shimizu, Masahiro Terada, and Seiji Nakao “Gaudobukku ga hiraku minzokushi no shinkyouti: burukinafaso wo kuu wo megutte (Guidebook as an Ethnography: A ‘Triangulogue’ on Takao Shimizu’s Swallow up! Burkina Faso! ガイド・ブックが拓く民族誌の新境地『ブルキナファソを喰う!』をめぐって), Humanity & Nature News, 78, 2019, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, in Japanese.

—

1 Haruki Murakami and Mueko Kawakami, Mimizuku wa tasogare ni tobitatsu (The Owl Takes Off in the Twilight (みみずくは黄昏に飛びたつ), Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2017, in Japanese.